The Effects of Mindfulness-Based Interventions on Depression: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Your research proposal should be in correct APA 7 format. The paragraphs are indented and lines are double-spaced.

The introduction should include the following:

- Introduction to the topic of interest.

- Define key terms.

- What is known already - literature review of relevant findings (brief and focused) and previous reviews on the topic.

- Highlight area where there is missing information in the literature and how your systematic review will fill the gap.

- State the aims of this systematic review what the systematic review is going to find out, and how this is going to be achieved.

- Impact - this is where you indicate how the review will substantially add to science, change practice, save money and best of all save lives or improve quality of life in substantial numbers of people. Include an economic impact if relevant. The background should not be an exhaustive literature review. At the end the reader should have a clear idea of the research question, an understanding that it is original and relevant, and how this systematic review will help fill the gap in the literature.

Aims/Objectives

Clear statement of objectives of the systematic review

Research Question(s)

Include a clearly defined research question or multiple research questions here

Proposed Method

Design

- Describe the type of systematic review (e.g. meta-analysis)

- Describe which guidelines you will follow (e.g., PRISMA guidelines).

Eligibility Criteria

- Describe the inclusion criteria for the papers of your systematic review

- Describe the exclusion criteria for the papers of your systematic review

Search Strategy

- Which databases will you use?

- What search terms will you use.

Study Selection

- Describe how data will be exported and which reference manager (e.g., Zotero) will be used

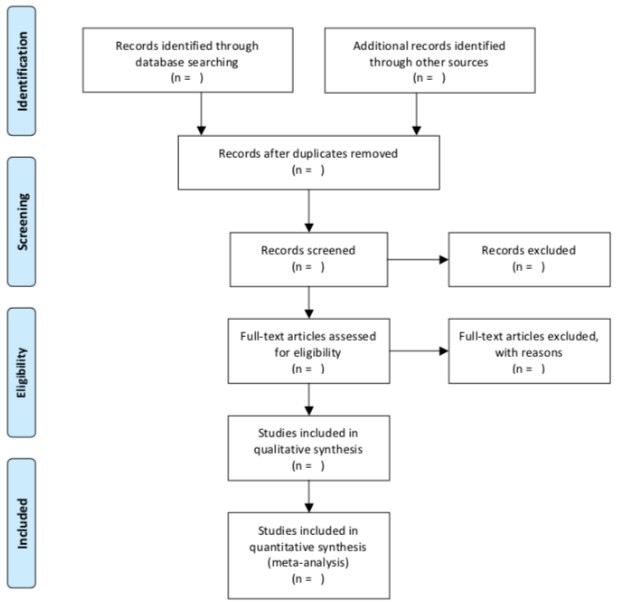

- Explain which PRISMA Flow Diagram will be used and the selection process

Date Extraction

- Explain which study characteristics and data will be extracted. Provide the data extraction form or file in Appendix or upload it to the assignment provided in Moodle. Make sure that the data extracted is sufficient to answer the research question(s).

Proposed Data Analysis

Quality Assessment

- Make clear which quality assessment tool you will use and how you will use it. You might use different quality assessment tools for different types of studies.

- Justify why it is the most appropriate quality assessment tool for your systematic review.

- Provide the quality assessment tool in Appendix or upload to the assignment in Moodle.

Data Analysis and Synthesis

- Make clear which data will be reported and how

- Make clear how the data analyses, synthesis and reporting of data will answer the research question(s)

- Potentially provide example tables to show how data will be reported.

- If you are planning a meta-analysis or multiple meta-analyses make sure it is clear: 1. Which effect size(s) will be reported; 2. Which analysis or analyses will be done and which software or files will be used; 3. How the data will be presented; 4. How will you check for publication bias.

- If you are not planning a meta-analysis make clear why a meta-analysis is not suitable for your systematic review.

How Does Athletic Identity and Involuntary Retirement Affect Post-Retirement Outcomes in Elite Athletes? A Systematic Review

Athletic retirement is described by the transition process from participating in a competitive sport to a post-athletic career (Willard & Lavallee, 2016). Every athlete experiences retirement differently and their transitional process is influenced by many factors unique to the individual athlete (Willard & Lavallee, 2016). The experience of the post-transitional process out of sport depends on three factors; characteristics of the athlete (e.g., age, gender, past transition experience); characteristics of the transition (e.g., onset, degree of stress, and role change); and characteristics of the pre- and post-transition environments (e.g., physical setting, organizational support, and personal support systems) (Willard & Lavallee, 2016). Transitioning out of sport can demonstrate changes in their social, financial, psychological, and occupational lives. Unlike other careers of workforces, retirement from sports is seen to occur earlier in life (Smith & McManus, 2008). Athletic retirement can be put into two categories: athletes who retire voluntarily and those who retire involuntarily, in which involuntary retirement is demonstrated to be the most concerning (Webb et al., 1998). Voluntary retirement is associated with less difficult adaptation to life after sports in elite athletes (Hatamleh, 2013). Whereas, many athletes experience short sporting careers due to involuntary retirement due to exposure to a career-ending injury or illness (Bernes et al., 2009). When athletes are forced into early retirement they are often not prepared psychologically to cope with the loss of their career (Bernes et al., 2009). With involuntary retirement, athletes may face a lack of psychological control over their own life outcome which can affect their response to the transitional process (Webb et al., 1998). Therefore, retirement can be traumatic and challenging on an athletes transitional process out of sports and can lead to a loss of purpose and identity (Bernes et al., 2009). Research suggests that athletic retirement is different than other career retirements because of the age, intent, and unpredictability of forced retirement (Smith & McManus, 2008). Involuntary retirement from sports is demonstrated to cause more psychological difficulties than other careers, because for the general population retirement may exhibit excitement to begin their next chapter in life (Smith & McManus, 2008).

Post-Retirement Mental Health Outcomes

Involuntary retirement is shown to cause negative post-retirement outcomes such as poor psychological well-being and long-term adverse mental health outcomes (Esopenko et al., 2020). The mental health outcomes that athletes may experience following involuntary retirement are symptoms of depression, distress, sleep disturbances, substance abuse or dependence, poor quality of life, negative nutritional behaviours, and a decrease in life satisfaction than athletes who retire voluntarily (Esopenko et al., 2020; Gouttebarge et al., 2019). The prevalence of mental health symptoms and disorders in retired athletes was 26% for anxiety and depression, and 16% for distress (Gouttebarge et al., 2019). Previous literature investigated 219 former athletes across 11 countries and found that 35% reported experiencing symptoms of anxiety or depression (Sanders & Stevinson, 2017). A systematic review and meta-analysis by Gouttebarge et al. (2019) examined 15 studies that related to mental health symptoms and disorders in both male and female retired elite athletes. Gouttebarge et al. (2019) found out of 6,563 retired elite athletes that 15.8% reported distress symptoms, 26.4% reported anxiety or depressive symptoms, 20.9% reported sleep disturbances, and 21.1% reported alcohol misuse. They also found that during the transitional process, athletes commonly experience emotional loss due to the loss of support systems from their sports, such as their teammates and coaches. Furthermore, athletes can face challenging self-concept difficulties when forced to retire, such as losing their athletic identity (Martin et al., 2014).

Athletic Identity Post Involuntary Retirement

Athletic identity is defined as the extent to which an individual identifies as an athlete and considers their athletic role as an important part of their self-concept (Martin et al., 2014). Athletic identity can be seen as a multi-dimensional construct that includes social, cognitive, and affective foundations (Lamont-Mills & Christensen, 2006). Athletic identity is a desirable quality as it is positively related to sports performance (Martin et al., 2014). Previous research demonstrates that athletic identity decreases after retirement from sport, and this decline is associated with the promotion of life post-sport (Martin et al., 2014). Involuntary retirement from sports requires athletes to cope with adjustments to their physical, personal, social lifestyle, and identity (Wylleman et al., 1999). The identity process adjustment focusses on recovering from a negative and distressing response to athletic retirement (Lavallee et al., 1997). Athletes quality of adjustment to retirement increases while their athletic identity decreases when they successfully cope and adapt to their career termination (Lavallee et al., 1997). Past research has suggested that the strength of an athletes identity directly influences the identity difficulties they experience following their retirement from sports (Willard & Lavallee, 2016). Longitudinal studies suggest that athletes who had a weak athletic identity, experienced a positive transition following their athletic retirement (Lavallee et al., 1997). Whereas, athletes with a strong athletic identity demonstrate a restricted evolution of a multidimensional self, adjustment issues post-retirement, post-injury emotional distress, social isolation, and career maturity delays (Martin et al., 2014). Furthermore, athletes with a strong athletic identity who retire involuntarily were found to experience depression, dissatisfaction, and loneliness (Lavallee et al., 1997; Sanders & Stevinson, 2017). Therefore, athletic identity is considered to be a crucial factor that can influence an athletes post-transition experience (Willard & Lavallee, 2016).

There is research that demonstrates that athletic identity and involuntary retirement has an impact on post-retirement outcomes, however there is no previous research that provides a comprehensive and unbiased overall summary of available evidence on the impact of involuntary retirement on athletic identity levels in retired elite athletes. A systematic review on this topic can highlight areas where further research and resources are necessary, which can be an essential resource for clinicians, researchers, and policymakers.

Rationale

It is important to research the concept of athletic identity among retired elite athletes as involuntary retirement from sport can be a challenging and potentially traumatic experience. When athletes retire, they have a risk of developing mental health difficulties and isolation due to the loss of social and emotional relationships that are associated with being part of a team. Retirement from sports can also lead to a loss of personal identity, particularly if the athlete has strongly identified with their athletic identity (Willard & Lavallee, 2016). This systematic review on athletic identity can help retired athletes understand their post-athletic identity and how they can find new sources of meaning and purpose in their lives. In addition, understanding the factors that influence athletic identity and how it evolves over time can help coaches, family, and other stakeholders in sports create a more supportive and healthier environment for athletes. Lastly, this review can inform interventions aimed at supporting athletes through the retirement transition process and help them navigate the challenges that come with this major life change.

Aims/Objectives

The main aim of this study will involve a rigorous and systematic search for all relevant studies on involuntary retirement due to injury or illness and whether athletic identity affects post-retirement transitions in athletes who have retired. Followed by appraisal of the quality of the studies, and synthesis of their findings in order to identify the overall impact of involuntary retirement.

Research Questions

The research questions I will be investigating in this review are:

1.How does involuntary retirement affect athletic identity?

2.How does athletic identity influence post-retirement outcomes?

3.Does athletic identity moderate the relationship between involuntary retirement and post-retirement outcomes?

Proposed Method

Design

This study will be a systematic review and narrative synthesis analysis as these methods provide the most comprehensive and objective approach for reviewing literature on athletic identity in athletes who have retired involuntarily. This review will be administered according to the recommendations in the Preferred Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) checklist (Moher et al., 2009; Appendix A).

Eligibility Criteria

Studies will be included in the review if they meet the inclusion criteria which have been developed by investigating past research. The inclusion criteria include: (1) elite or professional athletes who have retired involuntarily, (2) athletic identity, (3) involuntary retirement due to injury or illness, (4) participants of any age and gender, and (5) non-Randomized Control Trials (non-RCTs) (e.g., controlled, observational, case-control, quasi-experimental studies).

Studies will be excluded from the review if they include: (1) non-elite or -professional level athletes, (2) athletes who have retired voluntarily from their sport, (3) systematic reviews, (4) RCTs, and (5) studies will be excluded if they are not published in English.

Search Strategy

A systematic literature search will be conducted from date using the following databases hosted by EBSCOhost: MEDLINE Complete, PsycINFO, SPORTDiscus, and Academic Search Ultimate. These specific databases will be used because they include articles from journals in psychology and behavioural sciences, and on sports psychology which embody athletic identity. The search terms that will be searched in titles and abstracts in articles by also using Boolean operators will include: (elite athlete* OR professional athlete* OR sportsperson*) AND (athletic idenit* OR sport* identit*) AND (retire* OR involuntary retirement OR forced retirement) AND (injur* OR illness*) AND (post-retirement outcome* OR mental health OR MH OR mental health issues OR mental health difficulties OR mental health problems).

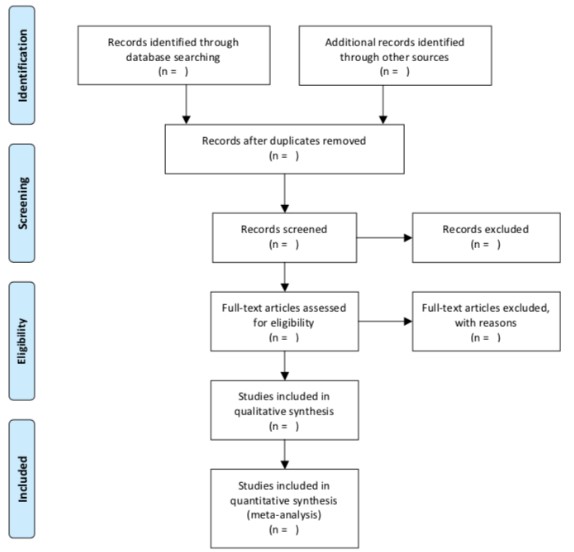

Study Selection

Once searches have been conducted, references from the search results will be exported to Zotero, which is a an open-source reference management software manager that helps collect, organize, annotate, cite, and share research. Once duplicates are removed, screening will be conducted on all titles and abstracts based on the inclusion criteria. Then, the study selection process will be conducted only by the author. The process will be displayed in the PRISMA flowchart (see Figure 1), which will include the number of studies identified, eligibility of inclusion and exclusion, and specific reasons for exclusion (Moher et al., 2009).

Figure 1

PRISMA

Flowchart

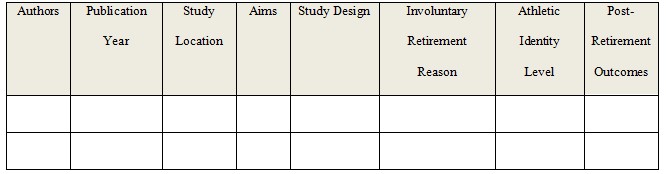

Data Extraction

Study characteristics and data will be extracted independently by the author using a data extraction form in excel (see Appendix B). The study characteristics that will be extracted are the following: study information (authors, year, country), study population (sport), study type, study aim, study location, involuntary retirement reason, athletic identity outcome, MH outcome from transition, sex, sample size, age ranges, type of analysis, themes, effect sizes, and implications of statistical significance.

Proposed Data Analysis

Quality Assessment

The methodological quality of the studies included will be assessed by the author using the Risk of Bias in Non-Randomized Studies - of Interventions (ROBINS-I). The ROBINS-I will be the quality assessment tool I will be using because it is the most appropriate tool to assess the risk of bias in the results of non-RCT studies (Sterne et al., 2016). The following seven domains will be examined: (1) bias due to confounding, (2) selection bias, (3) bias in measurement classification of interventions, (4) bias due to deviations from intended interventions, (5) bias due to missing data, (6) bias in measurement of outcomes, and (7) bias in selection of the reported results (Sterne et al., 2016). The ROBINS-I provides signaling questions which flag answers that have a potential for bias and can assist with reaching risk of bias judgements (Sterne et al., 2016). Therefore, this tool can provide a systematic way to organize and present evidence in relation to risk of bias in the non-RCTs of the effects of interventions (Sterne et al., 2016).

Data Analysis and Synthesis

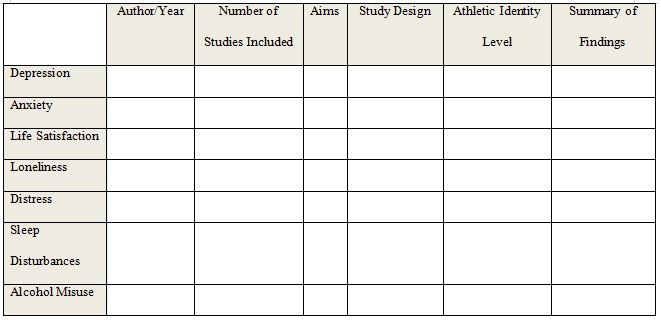

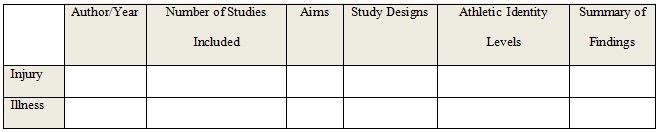

A narrative synthesis will investigate the evidence that demonstrates how involuntary retirement and athletic identity influences the transition out of sport, and port-retirement outcomes in former elite athletes. The data will be reported by using the data extraction tool in Appendix B. Research question one will be answered by finding data on study aim, reason for involuntary retirement (injury or illness), athletic identity outcome, sample size, type of analysis, themes included if qualitative, effect size, implications. Both research questions two and three will be answered by finding data on study aim, reason for involuntary retirement (injury or illness), athletic identity outcome, sample size, type of analysis, themes, effect size, and implications. Other information such as study information, study population, study design, study location, sex, and age can assist in understanding whether there are any similarities or differences in specific populations.

A narrative synthesis will be conducted as this approach focusses on the systematic review and synthesis of findings from various studies and relies mainly on the use of text and words to explain and summarise the findings of the synthesis (Popay et al., 2006). A meta-analysis will not be conducted due to heterogeneity of the included study design, study outcomes, and number of studies (Nordmann et al., 2012). Moreover, a meta-analysis requires an adequate number of studies which includes compatible data and statistical measures, however there are insufficient number of studies in this review, so a narrative synthesis best suits this systematic review (Nordmann et al., 2012). The studies included in the review are too diverse and therefore a meta-analysis might be meaningless, and therefore legitimate differences in effects could be concealed (Nordmann et al., 2012). In this current review, possible themes may appear so finding commonalities between the studies will be reported. Reporting of the data will be explained and summarised in the tables presented below.

Table 1. Summary of how involuntary retirement and athletic identity affects post-retirement outcomes

Table 2. Summary of themes: post-retirement outcomes

Table 3. Summary of themes: Injury vs. Illness

Examining E-therapy for the Treatment of Eating Disorders: A Systematic Review & Meta-Analysis

Eating disorders (EDs) are psychiatric disorders characterised by disturbances in attitudes and behaviours surrounding eating, and body weight and shape (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013). There are three main diagnostic categories for EDs: anorexia nervosa (AN) which is characterised by significant low body weight and an intense fear of gaining weight; bulimia nervosa (BN) which consists of recurrent episodes of binge eating followed by purging behaviours (e.g., vomiting, use of laxatives or diuretics, and excessive exercise); and binge-eating disorder (BED) which involves frequently eating excessive amounts of food that results in distress for the individual (APA, 2013).

Unfortunately, most people with EDs do not engage in treatment, as it is estimated that less than 25% of individuals with EDs seek treatment (Hart et al., 2011; Kazdin et al., 2017). This has been attributed to numerous reasons including being unaware of the severity of their condition, lack of knowledge around treatment services, stigma and shame about seeking treatment, and concerns about anonymity. Additionally, there are issues around cost, transportation, and lack of time associated with accessing treatment (Ali et al., 2017). A potential solution to overcome this treatment gap is through e-therapy, which refers to therapy that is delivered with a computer or smartphone and usually requires the use of the internet (Loucas et al., 2014). E-therapy has gained momentum as a potential solution because it can deliver an accessible and, at times, an anonymous service that is cost- and time-efficient (Burns et al., 2009; Donker et al., 2015; Warmerdam et al., 2010). Given that e-therapy is increasing due to technological advances and its potential solution in reducing the treatment gap for individuals with EDs, it is important to explore the literature on e-therapy for EDs (Loucas et al., 2014).

Efficacy of E-therapy for the Treatment of Eating Disorders

In determining the efficacy of e-therapy for the treatment of EDs, mixed results have been found, with some reviews suggesting it is promising (e.g., Aardoom et al., 2013; Dlemeyer et al., 2013; Haderlein, 2019), while others are more hesitant (Anastasiadou et al., 2018; Loucas et al., 2014; Pittock et al., 2018). A potential reason for these inconsistent findings includes reviews focusing on specific modalities of e-therapy, such as either computer-based e-therapies (e.g., Aardoom et al., 2013; Dlemeyer et al., 2013; Pittock et al., 2018), or mobile-based e-therapies (Anastasiadou et al., 2018). Further, many reviews have adopted strict inclusion criteria in which they excluded therapist-delivered e-therapies or studies that compared e-therapy to face-to-face therapy (e.g., Barakat et al., 2019; Haderlein, 2019; Loucas et al., 2014). Thus, many reviews have failed to provide a comprehensive overview of e-therapy for EDs.

To date, only one systematic review (Schlegl et al., 2015) has differentiated between the modalities of e-therapy in examining all types of computer-based and mobile-based e-therapies for the treatment of AN and BN. Computer-based e-therapy consists of interventions that are commonly delivered via a computer, whereas mobile-based e-therapy consists of interventions that are only delivered via a smartphone, and may include the use of smartphone applications, text messaging, and vodcasts (Anastasiadou et al., 2018).

Computer-based e-therapy is further divided into unguided, guided, and therapist-delivered e-therapy based on the amount of guidance participants receive (Schlegl et al., 2015). Unguided e-therapy involves the use of self-help programs for individuals to complete independently without the assistance of a therapist (Schlegl et al., 2015). Guided e-therapy involves ongoing support from a therapist whilst the client completes self-help programs (Marks et al., 2007). Finally, therapist-delivered e-therapy involves the therapist delivering the intervention via such methods as email, chat rooms, and videoconferencing (Schlegl et al., 2015).

Schlegl et al. (2015) examined 40 studies consisting of both randomised controlled trials (RCTs), controlled studies, and uncontrolled studies to provide a comprehensive overview of all e-therapies. Overall, they found that unguided e-therapy was not effective, but guided e-therapy appeared promising. Preliminary support was found for therapist-delivered e-therapies and mobile-based e-therapies, though more studies were needed to provide further evidence for their use. Whilst these results appear encouraging for the use of e-therapy, they cannot be generalised to all ED diagnoses as this review only investigated individuals with AN and BN.

Predictors, Moderators & Mediators That Impact the Efficacy of E-therapy For Eating Disorders

Many previous reviews have failed to focus on predictors of treatment outcome and dropout, as well as moderators and mediators, which impact the efficacy of e-therapy for EDs. Predictors are baseline variables which affect treatment outcome and may include variables such as age, sex, and ED diagnosis (Kraemer et al., 2002). Similarly, moderators are baseline variables which interact with the particular e-therapy intervention to affect treatment outcome and may include variables such as intervention length and clinician support (Kraemer et al., 2002). In contrast, mediators are variables that intervene between the commencement and end of treatment that affect treatment outcome and may include changes in the therapeutic alliance or early symptom change (Kraemer et al., 2002).

Only two systematic reviews (Aardoom et al., 2013, Schlegl et al., 2015), and a follow-up review by Aardoom et al. (2016) have investigated predictors of treatment outcome and dropout. E-therapy was more effective for individuals with less psychiatric comorbidity, that have BED rather than BN, and have higher motivation and adherence to treatment (Aardoom et al., 2013; Aardoom et al., 2016; Schlegl et al., 2015). In contrast, people were likely to drop out of treatment if they lacked motivation, had high levels of anxiety, depression, and ED symptoms, and experienced computer-related difficulties (Aardoom et al., 2013; Aardoom et al., 2016; Schlegl et al., 2015). However, these reviews did not examine all ED diagnoses and modalities of e-therapy which is needed to better understand which treatment program best fits specific clients and the major inhibitors affecting individuals from completing e-therapy.

Further, there is limited research on moderators and mediators, with only two reviews having focused on moderators of e-therapy. Barakat et al. (2019) found that increased use of multimedia was a significant moderator as it contributed to a reduction in ED symptoms. However, Melioli et al. (2016) found that ED symptom severity (non-clinical vs. high-risk populations) and the data analysis method (intent-to-treat [ITT] vs. completers) were not significant moderators for most outcomes assessing ED symptoms. Thus, there is a need to identify other moderators of e-therapy for the treatment of ED, such as potential therapist guidance. Moreover, no review has identified any mediators of e-therapy, with Aardoom et al. (2013) failing to find any studies that reported on mediation. Identifying mediators could be very useful in recognising the mechanisms of change, which are events and processes that happen within treatment that are responsible for a change in ED psychopathology (Kazdin, 2007). This could lead to improvements in treatment programs through increasing positive treatment outcomes.

Rationale

Given the lack of consensus between previous reviews regarding the efficacy of e-therapy for the treatment of EDs, it is important to conduct a review to clarify previous results. This study will expand on previous reviews by focusing on all modalities of e-therapy, including mobile-based e-therapies and computer-based unguided, guided, and therapist-delivered e-therapies, for the treatment of all ED diagnoses. As a result, this will be the first meta-analysis to focus on these particular modalities of e-therapy for the treatment of all ED diagnoses. Further, this review will identify predictors, moderators, and mediators in all modalities of e-therapy for EDs due to limited knowledge in these areas.

Information gathered from this review may provide greater evidence for the use of e-therapy for EDs. Specifically, this review may increase psychologists awareness of e-therapy for EDs and provide an overview of effective e-therapies that can be implemented in their clinical practice which deliver favourable outcomes to their clients. Additionally, e-therapy may be able to offer new ways for individuals with EDs to receive treatment, as it is readily accessible and less expensive compared to traditional face-to-face therapy (Andersson, 2016; Donker et al., 2015). Further, given this review will focus on predictors, moderators, and mediators, there is a chance that the findings could potentially lead to enhancements to the delivery of e-therapy.

Aims/Objectives

The main objective of the study is to update the overall efficacy of e-therapy for the treatment of EDs and compare the efficacy of each specific modality. Further, the secondary objective is to identify predictors of treatment outcome and dropout, as well as moderators and mediators, that impact the efficacy of e-therapy for the treatment of EDs.

Research Questions

The following research questions will be addressed by this review:

1 a) What is the evidence for the efficacy of e-therapy in reducing ED psychopathology among individuals with an ED?

b) Is there a particular modality of e-therapy that is most effective in reducing ED psychopathology?

2. What are the predictors of treatment outcome and dropout, moderators, and mediators that impact the efficacy of e-therapy for EDs?

Proposed Method

Design

This study will be a systematic review and meta-analysis as these methods provide the most comprehensive and objective approach for reviewing the literature on e-therapy for EDs (Gopalakrishnan & Ganeshkumar, 2013). This review will be conducted according to the recommendations in the Preferred Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) checklist (Moher et al., 2009; see Appendix A).

Eligibility Criteria

Studies will be included in the review if they meet the inclusion criteria which were developed after examining previous reviews (e.g., Aardoom et al., 2013; Anastasiadou et al., 2018; Schlegl et al., 2015). The inclusion criteria are as follows: (1) evaluate an e-therapy based intervention that is primarily delivered via the internet, computer, or smartphone for the treatment of EDs, (2) participants of any age and gender that meet criteria for a full or subthreshold ED diagnosis, including AN, BN, BED, Eating Disorder Not Otherwise Specified (EDNOS) or Other Specified Feeding or Eating Disorder (OSFED) according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) criteria (APA, 2013), (3) compare with a control condition (e.g., waiting list) or an active comparison (e.g., face-to-face therapy), (4) report pre-treatment and post-treatment outcome measure of ED psychopathology, and (5) is a RCT.

Studies that investigate e-therapy for the prevention or relapse prevention of EDs will be excluded due to considerable variation in how a prevention study is defined and outcomes used between studies (Melioli et al., 2016). Studies that are not RCTs (e.g., controlled, quasi-experimental, observation, case-control studies) will be excluded as RCTs provide the most reliable evidence regarding the efficacy of e-therapy for EDs (Hariton & Locascio, 2018). Further, studies published not in English will also be excluded.

Search Strategy

A systematic literature search will be conducted from December 2020 until February 2021 using the following four databases: PsycINFO, MEDLINE, Academic Search Ultimate, and PsycArticles (hosted by EBSCOhost). These particular databases will be used as they provide articles from journals in psychology and behavioural sciences which encompasses e-therapy. These databases will be searched by the author from inception up to the date the searches are conducted to provide a comprehensive overview of the literature. The search terms that will be used to source the articles are based on previous systematic reviews (e.g., Aardoom et al., 2013; Schlegl et al., 2015). These search terms will be searched in titles and abstracts and combined using Boolean operators: (online* OR computer* OR laptop OR e-mail* OR email, OR web OR internet* OR e-therapy OR e-health OR e-mental OR technolog* OR telehealth OR mobile* OR smartphone OR iCBT OR chat* OR video* OR sms OR text messag* OR software* OR CD-ROM OR self-help OR treatment OR program) AND (anore* OR bulimi* OR binge* OR EDNOS OR OSFED OR eating disorder* OR disordered eating OR body* image). Reviewed studies from previous reviews identified in the search will also be examined for inclusion. To minimise publication bias and ensure a comprehensive search is undertaken, additional searching on www.clinicaltrials.gov, www.worldcat.org, www.opengrey.eu, and https://psyarxiv.com for unpublished and pre-published trials will also be carried out. Further, authors who have been most prolific in the field of e-therapy for EDs will be contacted for unpublished studies.

Study Selection

After the searches have been conducted, references from the search results will be exported to Zotero, which is a referencing manager used to file references and identify and delete duplicates. Once duplicates are removed, all titles and abstracts will be screened for eligibility based on the inclusion criteria. Full-text papers of any titles and abstracts considered to be eligible will be acquired and examined for inclusion into the study. The study selection process will be performed by the author only. The process will be outlined in the PRISMA flowchart (see Figure 1), which details the number of studies identified, included and excluded, and reasons for exclusion (Moher et al., 2009).

Figure 1

PRISMA Flowchart

Data Extraction

Study characteristics and outcome data will be extracted independently by the author using a data collection form (see Appendix B). The following study characteristics will be extracted: study information (authors, year, country), study population (ED diagnosis, number of participants, age, sex), intervention design (type of modality of e-therapy, program outline), control/comparison intervention, length of intervention (weeks), follow-up time (months), outcome measure of ED psychopathology, and treatment dropout (i.e., percentage of participants not finishing treatment in the intervention group). Information to calculate effect sizes will be extracted for the following outcomes of ED psychopathology: global measure of ED psychopathology, frequency of binge eating and purging (i.e., the number of objective binge eating and purging episodes over the past 28 days; Fairburn & Beglin, 1994), and dietary restriction. Predictors of treatment outcome and dropout and moderating and mediating variables will also be extracted.

Proposed Data Analysis

Quality Assessment

The methodological quality of the included studies will be assessed by the author using Version 2 of the Cochrane Risk-Of-Bias Tool for Randomised Trials (Higgins et al., 2019). This particular quality assessment tool will be used because it is the most appropriate and up-to-date tool to assess RCTs. The following five domains will be examined: (1) bias arising from the randomisation process, (2) bias due to deviations from intended interventions, (3) bias due to missing outcome data, (4) bias in measurement of the outcome, and (5) bias in selection of the reported results. This tool contains a series of signalling questions which elicit information from the study that are relevant to each risk of bias domain. Once the signalling questions are answered, each domain is judged as having low, high, or unclear risk of bias. An overall risk of bias judgement is also given for each study comprising low, high or unclear risk.

Data Analysis and Synthesis

Research Question 1

A meta-analysis will be conducted to examine the efficacy of e-therapy for the treatment of EDs. The results will be illustrated in a series of forest plots to show individual and combined effect sizes and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Analyses will be computed for all e-therapy interventions, with subgroup analyses for mobile-based e-therapies and computer-based unguided, guided, and therapist-delivered e-therapies. Effect sizes will then be compared to determine whether a particular modality of e-therapy is most effective in treating EDs. Analyses will be performed at post-intervention, short-term follow-up (<6>

Between-group effect sizes and corresponding 95% CIs will be calculated at post-treatment and follow-up using Psychometrica online calculation tool (https://www.psychometrica.de/effect_size.html; Lenhard & Lenhard, 2016). Studies in which relevant data is available, effect sizes will be calculated according to Hedges g based on means, standard deviations, and sample sizes reported within studies (Hedges, 1981). If such data is not available, t-statistics, F-statistics, or the effect size reported in the study will be converted to Hedges g using the Psychometrica online calculation tool (Lenhard & Lenhard, 2016). If needed, authors may be contacted to provide further information to calculate effect sizes. When available, ITT data will be used to calculate effect sizes. Hedges g will be used as a measure of standardised mean difference as it corrects for bias in small sample sizes (Lakens, 2013). The effect size will be interpreted as small (0.20), medium (0.50), and large (0.80) based on guidelines suggested by Cohen (1988). These guidelines will be used as this will be the first meta-analysis to examine these particular modalities of e-therapy for the treatment of all ED diagnoses. Positive g values will indicate that the e-therapy intervention is more effective in reducing ED psychopathology compared to the comparison.

Since high heterogeneity is expected across studies, with varied intervention lengths, follow-up times, and outcome measures used (e.g., Schlegl et al., 2015; Pittock et al., 2018), a random-effects model will be used. Statistically heterogeneity will be assessed using the I2 statistic which details the degree of heterogeneity among studies. An I2 value of 0% indicates no heterogeneity, with 25%, 50%, and 75% indicating small, moderate, and large levels of heterogeneity (Higgins & Thompson, 2002).

Research Question 2

Predictors of treatment outcome and dropout, as well as moderators and mediators will be synthesised descriptively, by reporting what the included studies found. Due to preliminary research into these variables and unknowns surrounding mediators of e-therapy for EDs, it is decided to synthesise the research descriptively. Predictors, moderators, and mediators will be presented for outcomes of ED psychopathology at post-intervention and categorised based on the type of modality of e-therapy. Any variables that produce a statistically significant positive, negative, or non-significant relationship to outcomes will be reported. For variables examined in two or more studies, the number of studies that find the same type of relationship to the outcome will be counted and subsequently reported. This will help to show the possible relationship between that specific variable and outcome.

Publication Bias

To assess publication bias, funnel plots will be produced for outcomes of ED psychopathology. Publication bias will be present if studies are asymmetrically distributed around the true underlying effect size (Borenstein et al., 2009). If signs of publication bias are present, the Trim-and-Fill Method will be used (Duval & Tweedie, 2000). The Trim-and-Fill method reports the number of missing studies that would be required to correct the asymmetry and re-estimates the effect sizes after adjusting for publication bias.

Are you struggling to keep up with the demands of your academic journey? Don't worry, we've got your back!

Exam Question Bank is your trusted partner in achieving academic excellence for all kind of technical and non-technical subjects. Our comprehensive range of academic services is designed to cater to students at every level. Whether you're a high school student, a college undergraduate, or pursuing advanced studies, we have the expertise and resources to support you.

To connect with expert and ask your query click here Exam Question Bank