Student Engagement And Barriers To Implementation: The View Of Professional And Academic Staff

- Country :

Australia

Introduction

The changing nature of higher education (HE) has been well documented by researchers who have identified that market pressures and the growing competitive nature of education provision has led to such institutes having to rethink how they strategically manage and view their students (Black 2015; Faizanet al. 2016). Imperative to this thinking, is the noticeable rise in the opportunities that universities now offer to their students for enhanced engagement. It has been recognised by researchers that student engagement (SE) has become an extremely important concept within HE, with regards to student achievement and learning and as such many universities are concentrating their efforts and resources in this area (Sinatra et al. 2015).

Understanding the scope of SE and defining what it means, has been a question raised by many (Trowler 2015). Boekaerts (2016) suggests that there is little consensus regarding the boundaries of engagement (77) and noted that there are varied differences in attempting to define SE. In simple terms, SE has been described as what university students do, or what is their involvement and commitment whilst in education (Hu, Ching, and Chao 2012). In attempting to address this issue, some researchers have suggested that SE is derived from the growing research around customer engagement and service quality and the emerging debate around students as customers (Guilbault 2016). It has been highlighted that many measures of SE, focus purely from an academic perspective, however, it is important to note that engagement at university involves many aspects of non-academic activity too. Acknowledging this, Trowler & Trowler (2010) in their report for the Higher Education Academy (HEA) stated that SE is concerned with the interactions between the time, effort and other relevant resources invested by both students and their institutions intended to optimise the student experience and enhance the learning outcomes and development of students and the performance, and reputation of the institution. (p.3)

It is clear that student engagement in all its formats is an incredibly important feature of the HE sector, and many engagement activities go beyond the classroom setting and as such many engagement activities offered within HE are delivered by professional staffff, for example through the library, health & wellbeing, marketing, careers and alumni. For the purpose of this study, the concept of SE will be considered as the initiatives made available to students whilst studying at university, including academic and non-aca demic opportunities.

Research into SE is often viewed from a students perspective, in particular related to student outcomes(Kahu 2013) however, it has been identifified that further research is needed to understand the opinions of staffff working within HE (Healey, Flint, and Harrington 2016). The rise in professional staffff within universities and the role they play in engagement activities is noticeable, yet this has caused tensions in some aspects of HE provision (Curran and Prottas 2017; Baltaru 2019). Professional staff for the purpose of this study are staff that work in a range of roles and service departments that offer support functions to students including: library, sport facilities, student union, marketing, careers, health and wellbeing, alumni, registry, and the international office. The role of professional staff within universities and how they are involved in the student experience, including SE initiatives is an area that has received growing interest recently. Evidence clearly indicates that the number of professional staff employed within the HE sector has risen in recent years (Frye and Fulton 2020) however, whilst extra resources are often appreciated, the role of academic staffff versus professional staffff has come under scrutiny. Roberts (2018) revealed the important role that professional staff in universities play with regards engagement and the students life-cycle within HE, suggesting that they have an important factor to play, but often this is an area that is underresearched as most studies focus solely on academic staff. Curran and Prottas (2017) revealed that one of the major concerns professional staff have is what their role is and how it is defifined. They identified that this is one of the major stressors that staffff complained about and hindered them doing their job. The diverse and broad array of engagement initiatives go beyond the classroom and academic input only and professional staffff now play an important role in many engagement pursuits and often underlying tensions exist within many universities questioning who is seen to have overall responsibility of such engagement. Baltaru (2019) endorses this issue, her research acknowledges that professional staffff work on the margins of academic staffff, leading to the distorting of boundaries, suggesting that universities need to look beyond their organisations purely from a teaching and research perspective. Whilst such frictions exist, the important role that professional staffff play within HE is apparent, yet often such staffff are not involved in research, thus many institutes fail to fully evaluate from varied perspectives. Professional staffff provide an important function in many modern universities and the services they provide are seen as a major part of the students journey whilst at university. Gaining opinion and views from both staffff groups is essential to understand their views on the types of engagement activity they may be involved in and what their views are regarding student engagement (Roberts 2018).

The advantages of students participating in engagement initiatives have been well documented andDumford and Miller (2018) acknowledge that there are numerous benefifits to not only students but other associated stakeholders too, for example the local community, employers and society. However, researchers have identifified that there has been limited investigation regarding the study of potential barriers to staffff being able to offffer SE initiatives (Aljo hani 2016). Previous studies have explored problems of students not being able to access such activities, but very little research has been undertaken to explore any potential barriers that may stop staffff from being able to deliver SE opportunities (Freeman and Simonsen 2015).

This study will explore two research aims namely: what engagement initiatives are offffered by academic and professional staffff at university and what barriers prevent them from being able to deliver such opportunities (Boles and Whelan 2017). Gaining such insight from academic and professional staffff will address the issues and questions raised, that will hopefully help inform HE providers with a more evidence-based insight into how to alleviate some of the concerns raised.

Methodology

Participants were recruited from staffff employed at a Post-92 university within the UK, using a convenience sampling technique, which is common in studies on engagement (Fernandes and Esteves 2016). The staffff were purposively selected from a range of departments, using criterion sampling (Veal and Darcy 2013) based upon them having to have been employed by the university for at least six months and have working knowledge of the student experience within their remit. All staffff were chosen based upon them being involved in or responsible for engagement activities for the university. It has been acknowledged that undertaking research within a setting that the researcher is known can have both advantages and disadvantages (Coghlan 2007).

Greene (2014) suggests that this form of research which is often undertaken via qualitative studies is often referred to as insider research, which she advocates as the study of ones own social group or society (1). Teusner (2016) suggests that in recent years, insider research has come under increasing scrutiny regarding validity as the researcher she suggests, is an actor within the research setting and as such the issues of subjectivity and control comes into question.

Hence, being aware of the potential hazards to reduce the impact as outlined by Fleming (2018) was considered, including minimizing the potential for implicit coercion of participants; privacy and confifidentiality; identifying potential biases and being aware of the potential of professional conflflicts in the dual roles of being an academic and researcher within the same context (319320).

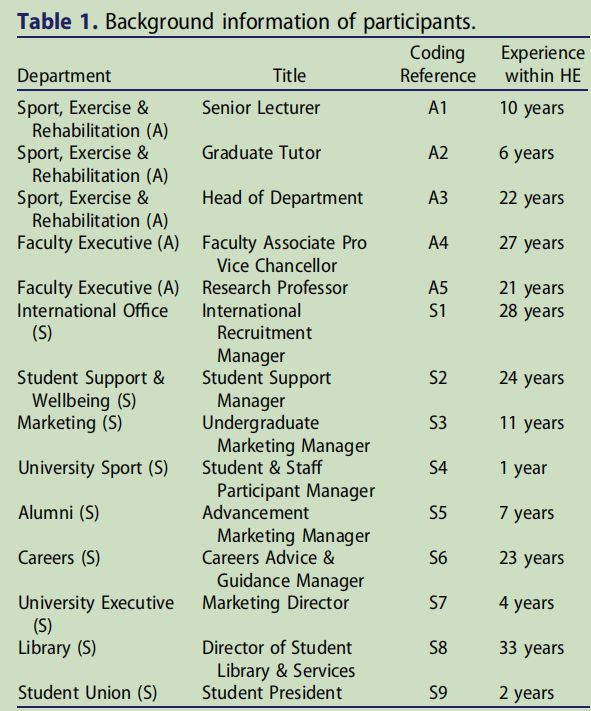

Fourteen staffff, including academic and professional staffff, were interviewed from various departments within the university including academic (A) and ser vices (S) (refer to Table 1). Five participants were academic staffff, and 9 participants were professional staff. The participants experience of working within HE ranged from 1 year to 33 years, averaging 15 years in total. All the participants had a role in working with students and all were involved in various aspects of student engagement.

The interviews were recorded and transcribed to ensure an accurate report and record of the information collected. The data was then coded and themes and patterns were identifified (Glaser and Laidel 2013; Lawrence and Usman 2013). Care was taken in the coding exercise to ensure that the themes were not underdeveloped as Connelly and Peltzer (2016) suggest that often analysis of qualitative data is not fully analysed, leading to a lack of substantive fifindings, with little relevance to the research aims.

To ensure deep and meaningful codes were established, the researcher read the transcripts numerous times to safeguard an in-depth scrutiny of the investigation.

Results

It was clear from the results that all staffff interviewed considered they had a role to play in SE within the different positions they held. The view that engagement was about how students immerse themselvesin the various initiatives that are offered by universities, both academic and non-academic throughout the course of their time at university was another point that was raised, suggesting I think the key thing for me is they are touching our people and our services and facilities every minute of every day throughout the whole time they are with us (S8).

Typically for me an engaged student would be somebody who attends seminars and lectures, not just attends but also gets involved in the sessions and offers insightful comments and steers discussion.

Someone who goes out of their way and has done extra reading. Also be involved in volunteering, work experience, being part of a sports team or being a rep (A2) I think an engaged student is one that doesnt just see them coming into the university to do their degree, do their course and then go home. I think an engaged student is one that is involved in various different aspects of the university, whether that is sport related or whether it is something to do with the students union and societies (S5)

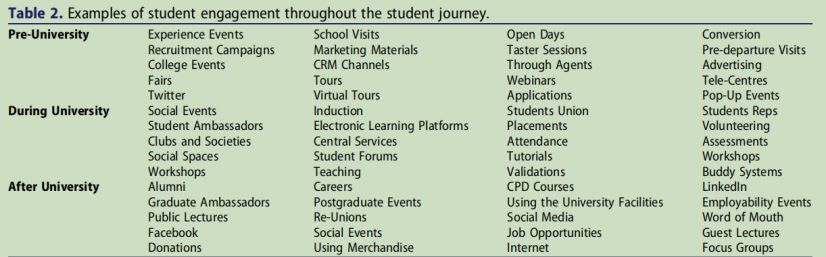

When staffff were asked how they are involved in SE (refer to Table 2) many initiatives stated clearly demonstrated a commitment to engage with students throughout the lifetime of the student journey, namely, before, during and after graduation. The breadth of activities also demonstrates the various input from both academic and professional staffff that can impact upon students studying within HE and the role that extra-curricular activities play in engagement initiatives. Such examples include the opportunity to engage in: sport; volunteering; student union clubs and societies; campaigns; placements; social media; social events and other non-academic activities.

Barriers to student engagement

Whilst many advantages associated with SE were acknowledged (including benefifits to an individual student, university and society), the main barriers that staffff stated related to lack of resources, operational issues and problems associated with processes and systems.

Lack of resources

The majority of respondents stated that there were some constraints that impacted upon them being able to offer engagement opportunities to students, the main limitation being that of resources. Resourcing in terms of stafing and finding adequate spaces (S6), as well as having to reduce the cost per head that were investing in initiatives (S8). The element of time and how adaptable the university is, was also raised I think resourcing is a diffiffifficult one and I think there is a time element. We are always in a state of change and there is always a time elementto that (A3). It is about providing the staffff who we have with the right tools, including timing and resources (A3). The fifindings indicate that both academic and professional staffff stated that lack of resources was problematic to them being able to deliver engagement activities that they were involved in regardless of the activity.

Operational

Related to the resourcing issues mentioned above, participants suggested another problem related to engagement initiatives was the increase in students numbers and the resulting class sizes. Its more to do with the operational stuffff associated with it, how we manage a large organisation with many students and diverse programmes (A4). Some students will become dis-engaged because they have been lost in the system because we have expanded so much. If you have 30 students in your class, then there is a good chance you may know them, but if you have 150, it becomes less likely (A5).

In addition, the concept of staff buy in was stated with staffff suggesting that, it depends on the activities at an operational level, the people who are delivering the engagement activities; it is the people at the front end who have to deliver it and buy into it (A3). The first barrier, I suppose is about people buying into it, a common set of expectations that you can deliver (A4). I think it depends on people priorities, because faculties, but it depends on what they deem their pri orities are (S4). The findings present two concerns, namely the prioritization that is placed on such activity and how individual staffff then act upon those priorities.

Interestingly, the notion of student buy-in was commented upon as a potential barrier. I think sometimes lack of engagement lies with the student (S1) and sometimes there are limitations on how willing the student is to engage (S7). So there is often, I think, a mismatch between what students say they want to do and what they actually want to do and I have always found that frustrating (S2). I think its about students taking responsibility too, we are hereto help but they need to get enthusiastic and be part of it (A1).

Similarly, lack of awareness of initiatives was also mentioned by two people I would assume so, though Ive never actually been involved with it (student engagement), I dont know what we do around this, but I would like to think that we are engaging with them (A5). Rather alarmingly, this comment came from an academic, who is suggesting that they have never been involved in such activities, yet as part of their duties engagement is very much deemed an essential aspect of any academic job.

Processes & systems

An emergent theme related to barriers to SE was that of systems, processes and structures. Sometimes it can be difficult to work through different structures, you are not 100% sure on where things are, who you are supposed to talk to and what format it should be in (S9). With regards to universities and structures, it can be quite difficult to work with that, because things move quick so it is hard to keep up with what is needed (S6)

Another theme that emerged from the data related to a lack of coordination and a joined up approach to delivering engagement initiatives. I think sometimes it is just an operational one of how different parts of the university work together to coordinate better (S1) and we just need to work at coordinating things better, like the optimum way of communicating with students at the right time (A2). Trying to get everyone working together and respond quickly, as quickly as what students need us to, I think is a tricky balance (S5).

We need to join up the student journey; we have to work together more closely to understand where the student is sitting at any given point and who is engaging with them and why they are engagement with them. We need to make sure we dont all fifight over the student or stress them out, all shouting at once (S8)

Related to the lack of coordination is the notion of a potential disparity between strategic intention and operational capacity. It is a challenge; we can do the policies, but where the struggle is, is in the implementation (A4) and I think there is always a tension between what the strategic and operational is (A3).

Similarly, it relates to direction of policy around things such like student engagement, that has been pushed from the top without acknowledgement of what is happening at the ground level (A1).

I think the universities expectations are lower than ours on the programes. For example, you get 100 students, so tick; you have ten staff, so tick. So its like were efficient and were effective, we did it and we did it within budget. Did the students enjoy themselves; no, they hated it so it wasnt effective. We are measured on efficiency rather than effectiveness (A2)

Interesting to note, that all comments relating to lack of strategic intention and operational capacity were made solely from academics. The concept of centralisation also emerged as a theme and the notion that such a system in itself can create tensions, between not only the strategic policy makers and staffff working at the operational level, but also between the service departments and academic staffff.

There is a centralisation of services and a direction of policy around things like student engagement, they (services) say that if you do this, the student will be engaged, but actually we dont know that, because how it works (A3) Similar to the view of centralisation is the impact that a standardised approach is not always beneficial. The challenges that we face is that we decide on the policies and they are all very well and good, but the major challenge is the implementation in a standardised way (A4). One size is never going to fit all (A2).

I would say the university, I dont think it trusts, maybe that is too strong a word, but it doesnt trust the people who engage with students. So for example, how you engage with a sport management student is going to be different to how you engage a sport coaching student or a business student. It is all going to be difffferent, so I think a one size fifits all works against that (A1)

This notion that student cohorts are difffferent and the view that universities need to be mindful of the varied student typologies also emerged from the data. You have to fifind the balance for the individual, you cant do this (engagement) as a cohort, its a personal journey and we need to provide different services to support that (S8). You need to make engagement a lot more targeted, it can be a lot more tailored to the stage they are at, the degree, what entry level, that will make the experience a lot stronger (S3). Other suggestions were made related to the student age, the nationality of the student, and their home circumstances.

Its about the customer journey mapping, we need to look at what sort of person they are, what sort of things they need, what sort of adjustments and use all of this intelligence to build a service journey. At the end of the day when you know the student as an individual, you are more likely to achieve a meaningful engagement experience (S2) However, the question of having the ability to have a less standardised approach was raised in that we dont really have the capacity to be as personalised with each individual student as we would want (S3).

Also, how you get there without it being completely top down or just allowing everyone to do what they want, would cost us too much. You have to meet somewhere in the middle (A3). Whilst it has been acknowledged that understanding the difffferent needs of students and the diverse nature of the study body is extremely important, it is interesting to note that both academic and professional staffff recognise that due to resource constraints, this is not always feasible.

Discussion and practical implications The empirical fifindings clearly indicate that indeed there are many activities that HE institutes undertake to attempt to engage with their students and both academic and professional staffff play an important role in that delivery (Roberts 2018; Frye and Fulton 2020).

Wawrzinek, Ellert, and Germelmann (2017) suggest that universities provide a platform for students, but other stakeholders (academics and service departments) need to learn from each other in order to ensure that students receive effffective service quality that helps to co-create value. The lack of understanding and joined-up approach regarding the initiatives offered would suggest that this is not the case, which could result in ineffffective engagement strategies that do not deliver the intended aims, resulting in costly expenses and an inadequate use of limited university resources. Another major concern high lighted was the concept that many SE initiatives are generic and bearing in mind the changing nature of the student body (Black 2015; Faizan et al. 2016), it is not surprising to hear that HE staffff suggested that a one size fifits all is not effffective.

Whilst the fifindings raise interesting discussion, the views from bothacademic and professional staffff raise important issues that potentially impact upon HE students and engagement. Clearly, HE institutes need to be aware of their student population and their individual needs whilst acknowledging resource implications. As well as understanding student typologies, those responsible for SE need to consider the whole student journey and determine how such typol ogies engage throughout this timeline. Hence, it is imperative that academic departments and service departments work together in cooperation to ensure that SE initiatives are jointly understood and delivered.

It is apparent that the mapping of such activities and what their intended aims are, is often lacking hence, having an understanding of the student life cycle and when SE initiatives take place throughout that time period is essential to ensure that initiatives occur at the right time, duplication is avoided and the associated strategic aims are achievable. This exercise should be the responsibility of a SE working group and should be undertaken and reviewed annually in order to help overcome some of the operational issues and tensions.

The fifindings revealed that the issue of staffff buy-in is deemed essential to accomplish successful SE. Such priorities need to be led from positions of senior authority within universities to communicate the importance that is placed upon the associated SE strategic aims. Leading from the top of the organisation, with a senior member of the university executive having an assigned remit of SE will help to convey the important message that every member of staffff, both aca demic and professional have a role to play in engagement, regardless of the position they hold within the university. Also, university executive, indetermining their strategic direction need to ensure that they have the right resources, systems and processes in place to ensure effffective delivery, as well as ensuring that staffff who are implementing such initiatives are fully equipped and aware of what their roles are in helping to deliver the activities.