Assignment 2: Critical Review- Synthesising Research Evidence to Inform Practice

Introduction:

Paediatric Intensive Care Units (PICU) aim to provide supportive measures and life-sustaining treatments to those with critical illness or injury (Seino et al., 2019). Given todays medical advancements and technologies, more children are presenting to PICUs with more complex and acute illness (Iranmanesh et al., 2016). Each year, it is estimated that 2-10% of children admitted to PICU do not survive, thus acknowledging PICU as one of the most common locations for children to die (Butler et al., 2019). Whilst PICUs strongly advocate for directing care goals to that of a curative direction, as result of exhausted treatments, redirection of goals may be made to end-of-life care (EOLC) (Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Society (ANZICS, 2014). Children are often perceived as youthful and bound to live lengthy lives (Lewis-Newby et al., 2018), and as described by the ANZICS (2014), the death of a child is perceived as being unnatural. Consequently, recognising that a child is dying can be a highly emotional and traumatic experience for all those involved (Mu et al., 2019).

Background:

As described by the World Health Organisation (WHO) (2020), end-of-life care aims to promote enhanced quality of life (QOL), whilst forgoing life prolonging treatments in order to minimise pain and suffering. Despite the negative stigma behind EOLC, death and dying facilitated within PICUs should be treated as a human experience and not just a biological event (Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Healthcare, 2016). As stipulated by the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Healthcare (2016), EOLC should be perceived as a holistic approach that ensures comfort to both the child and their families when deciding to withhold or withdraw treatment.

Literature places emphasis on the life-long lasting impact a hospital admission can have on a family, however, more noteworthy is the life-long lasting impacts on bereavement that a poor EOLC experience can have on a family (Butler et al., 2019). Bereaved families are at higher risk for mental health complications such as anxiety and depression and posttraumatic stress disorders (Michelson, 2019). Whilst paediatric facilities are commonly described as caring for small adults, PICU when compared to adult ICUs are vastly different (Michelson, 2019). For example, adults are more likely to have self-advocated what QOL looks like for them and more likely to have a preconceived notion of death and dying (ANZICS, 2014). Whereas, PICUs present its own set of unique emotional burdens (Michelson, 2019).Whilst EOLC is noted to improve QOL in the acutely unwell child and reduced emotional burden placed on their families, it is too described to be the most ethically challenging choice made in PICUs by both health care professionals (HCP) and family members (Seino et al., 2019).

Aim:

The aim of this review is therefore, to explore the barriers to implementing EOLC in PICUs. Through systematic process, this review aims to utilise an integrative review to obtain the current literature available on EOLC barriers within PICUs. Subsequently, performing a thorough critical appraisal of the acquired research articles, identify major themes through thematic analysis and further discuss the findings. Throughout this integrative litertature review, the term child will be utilised to refer to individuals between the ages of four weeks old to 18 years old. Likewise, the term family will be utilised to refer to parents, grandparents, siblings or other individuals with significant relationship with the child.

Methodology:

Design:

In order to review the gathered literature, an Integrative literature review method was chosen. Given this review targets qualitative data, primary research and noted time constrains, an integrative literature review was deemed most suitable (Kutcher et al. 2022). Whilst a scoping review was considered, Munn et al. (2018) recommended that scoping reviews best identify key concepts and mapping of themes. In contrast, Silva, Brandao, & Ferreira (2020) eludes that an integrative literature review provides a methodical review of current knowledge/practice, analysis of primary literature and enables for enhanced translation of knowledge to practice. An integrative review was therefore deemed most suitable to aid the current understanding of current EOLC practices and perceived barriers, identity potential gaps or weakness in literature and address variation in knowledge with the aim to inform current practice or identify areas for further research (Munn et al. 2018).

Search Terms:

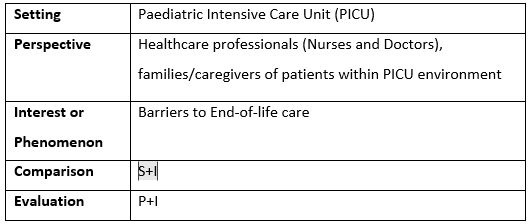

Given the identified research topic, the following Setting, Perspective, Interest or Phenomenon, comparison and Evaluation (SPICE) was formulated to compose the appropriate search strategy. The SPICE question framework was deemed most suitable given it enables a phenomenon to be explored in comparison to evaluate an intervention (Booth et al. 2018). Table 1 identifies the SPICE search strategy utilised for this review.

Table 1: SPICE

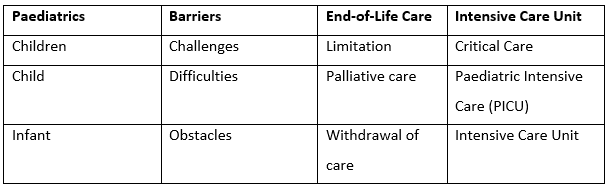

To begin identifying relatable search terms, a review of synonyms of the foundation key words depicted within the SPICE framework Paediatric, Barriers, End-of-Life care and Intensive Care Unit was undertaken. The following key words were identified as depicted in Table 2.

Table 2: Basic formulated search terms

Once the base terms for a search strategy were acquired, a pilot search was undertaken utilising the Flinders University database FindIt @ Flinders. Relatable studies of both grey literature and primary research were identified and a review of key words utilised within this literature assisted to expand the search terms and reach saturation of available research. The finalised search terms are displayed in Table 3.

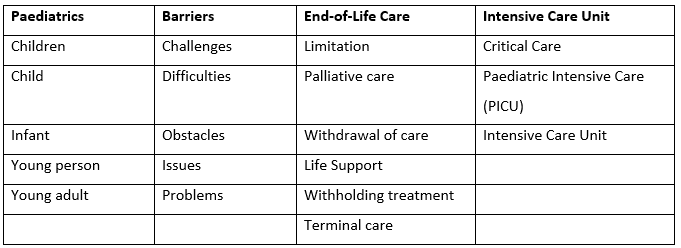

Table 3: Search terms

Young person Issues Life Support Young adult Problems Withholding treatment Terminal care Once search terms were finalised, three databases were selected based on their relevance in the chosen topic. The databases chosen were as follows; Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Scopus and ProQuest. These databases were chosen given their specific relation to health and medical based journals. Given the identified comparison intervention of the nurse role, CINAHL was specifically chosen given its specific audience of nurses and allied health (Wishart. 2012). Following this, Scopus was noted to have a large selection of journals including medical based (Elsevier, 2022). Furthermore, ProQuest was then selected given its large database comprising of both medical and non-medical journals and selected in anticipation to achieve a broader selection of data (ProQuest, 2022).

Utilising the above terms, search strings were placed into each database. Acknowledging that each database has varying search requirements, search strings were manipulated utilising truncations and Mesh terms depending on the database. These were utilised to ensure appropriate narrowing of request was undertaken. For example, the following string search was utilised and altered to individual databases:(Barriers OR challenges OR obstacles OR difficulties OR issues OR problems) AND "end of life care" OR "end of life" OR EOLC OR EOL OR "withdrawing treatment" OR withdrawal OR palliative care OR limitation OR "withholding treatment" OR "terminal care" OR "life support")) AND (paediatric* OR pediatric* OR children OR child OR young person OR young adult OR infant) AND ("intensive care unit" OR "intensive care" OR "critical care" OR PICU or ICU)

Eligibility Criteria

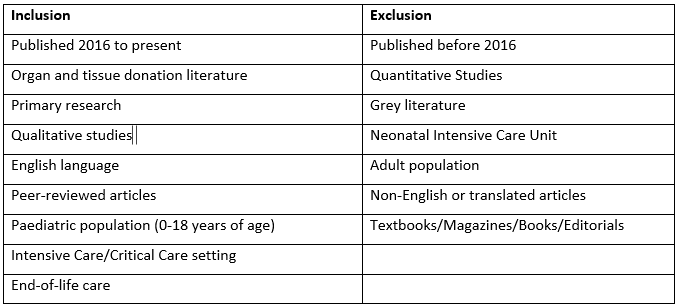

Once a detailed list of search terms was identified, an inclusion and exclusion criteria were formulated. By providing a clear and concise inclusion and exclusion criteria, research articles were able to be selected based on appropriateness and relevance in accordance with the chosen research topic. The inclusion and exclusion criteria utilised to aid in identifying relevant research studies is displayed in Table 4 below.

Table 4: Inclusion and Exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria displayed in Table 4, depicts what was considered as essential to achieve results that would aid in providing research articles relative to the chosen topic. Firstly, research articles were chosen if published from 2016 to ensure modernity of the perspectives on EOLC within the PICU. Solely primary, peer-reviewed qualitative research was chosen to review with the aim to obtain high quality, raw available research and data (Polit & Beck, 2017). Qualitative research was chosen over quantitative in order to grasp insight into the experiences and concepts of families and healthcare workers on the barriers of EOLC within the PICU.

The exclusion criteria display the criteria for removal of selected research. Quantitative research articles were deemed least suitable to gain insight, as it was considered as more than cause and effect is aimed to be investigated, in contrast, feelings, experiences and impacts on the perceived barriers are aimed at being investigated (Akinyode et al. 2018). Both NICU and Adult ICU settings were excluded given their variations in patient populations and models of care. Likewise, articles that were not primary research such as grey literature, magazines, books etc, were excluded in order to ensure only primary data was obtained (Polit & Beck, 2017). Finally, non-English and translated articles were excluded to prevent misinterpretation of analysis and results.

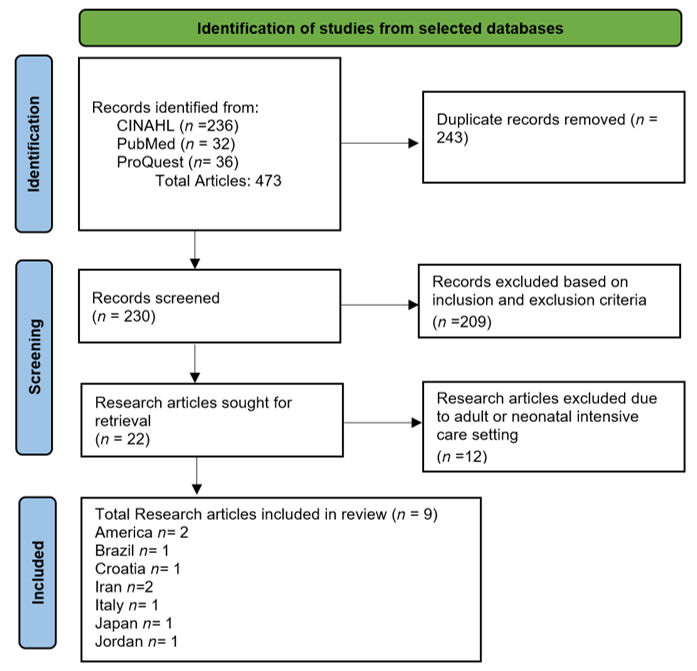

On completion of search strings in the selected databases, research titles were analysed and duplicated firstly removed, following this, the inclusion/exclusion criteria were applied to the research titles and narrowed. On completion, both abstracts and full texts were reviewed and results were finalised to eight qualitative research articles. Figure 1 displays the results of the database searches undertaken by using a PRISMA chart and application of inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Figure 1. PRISMA chart of search results obtained from database search

As displayed in the PRISMA chart in Figure 1, a total of nine relevant articles were selected based on selected inclusion and exclusion criteria. Whilst a total of 12 articles were excluded due to being solely focused on NICU population group, all articles identifying PICU within their population were selected. Given the small number of primary research articles identified, indicates a lack of research undertaken in the area, specifically regarding the EOLC in the PICU population. A summary of all nine articles can be found in Appendix 1.

Critical Appraisal

In order to effectively appraise the nine selected qualitative primary articles, The Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) was chosen. Utilising ten questions, the CASP tool is designed for health-related topics to appraise the strength, limitations and quality of evidence of qualitative research designs (Long, French, & Brooks, 2020). This appraisal tool was chosen given its clear, concise and systematic approach to reviewing a research article to evaluate the validity, results and relevance to the chosen topic (Long, French, & Brooks, 2020). The simplicity of the CASP tool, therefore, proved ideal for the novice researcher in order to identify the quality of the research. The CASP checklist can be found in Appendix 1 followed by Appendix 2 containing the results of the CASP checklist on the nine selected articles.

Results:

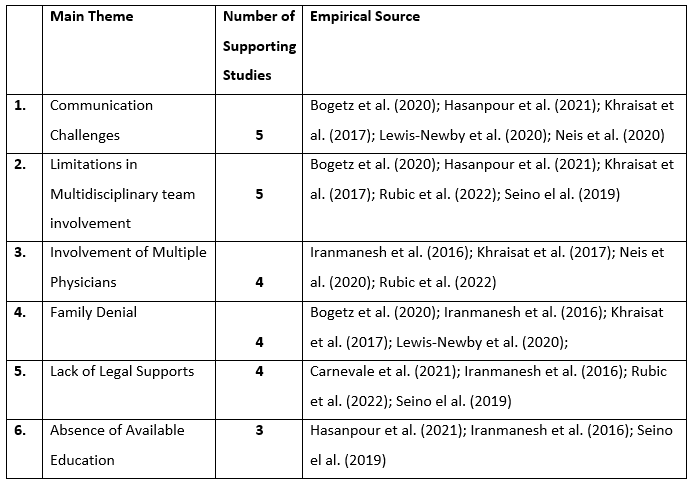

A thematic analysis was chosen to identify the main themes within the nine research articles. This analysis type was chosen as it was considered most appropriate to analyse the selected articles, identify patterns and formulate appropriate themes (Synder, 2019). Six main themes were identified through thematic analysis; Communication challenges, Limitations in multidisciplinary team involvement, Involvement of multiple physicians, Family denial, Lack of legal supports and Absence of available education. Each theme was supported by multiple articles. Table 5 exhibits the six identified main themes amongst the nine articles that are deemed relevant to the research topic, followed by a thorough analysis of each theme.

Table 5: Summary table of identified themes from research articles

Theme 1: Communication Challenges

Communication plays a vital role in ensuring families are equipped with the knowledge to make informed decisions (Hasanpour et al., 2021; Lewis-Newby et al. 2020). As discussed by five of the research studies, communication was identified as a barrier to implementing quality EOLC. Firstly, Bogetz et al. (2019) found that both non-verbal and verbal communication was crucial to conveying information to families. Correspondingly, Neis et al. (2020) discusses a family members experience where a physician was able to say the right things, however was described by the family member as lacking empathic body language resulting in a negative EOLC experience. Conversely, Hasanpour et al. (2021), found that HCPs found the complexities of personal protective equipment (PPE) as a significant barrier to providing sound communication to those families during COVID-19.

Healthcare professionals conveyed that more positive EOLC experiences were noted when communication was honest, inclusive of family and where appropriate key religious leaders or members of the community (Bogetz et al., 2020; Nei et al., 2020; Khraisat et al., 2017). Additionally, location of the conversations away from the bedside, utilising appropriate langue and ensuring families can explain their current understandings lead to more acceptance and openness from families (Lewis-Newby et al., 2020)

Theme 2: Limitations in Multidisciplinary Team Involvement

Providing holistic care through the use of multidisciplinary teams is the cornerstone to providing enhanced paediatric EOLC (Iranmanesh et al., 2016; Khraisat et al. 2017). An absence or limitation of access to multidisciplinary supports has been is identified as a barrier to implementing EOLC throughout five of the research articles. A multidisciplinary team involves access to social workers, psychologists and religious leaders (Iranmanesh et al., 2016). These supports were strongly identified as necessary components to supporting families during a highly stressful period (Seino et al., 2019). Without these supports, it was reported that nurses felt additional emotional burdens when caring for an acutely unwell child or multiple children, feeling as though they were unable to provide the support the families required (Bogetz et al., 2020; Hasanpour et al., 2021). Additionally, multidisciplinary supports were discussed as implementing the appropriately trained and culturally sensitive supports so family members did not feel alone when deciding to choose EOLC (Khraisat et al., 2017; Seino et al., 2019).

Theme 3: Involvement of Multiple Physicians

The complexities of PICU patients requires multiple medical specialty teams, particularly physicians, to ensure the best care is provided (Rubic et al., 2022). However, as identified by four studies, having multiple physicians involved is deemed a significant barrier to providing and implementing EOLC (Iranmanesh et al., 2016; Khraisat et al., 2017; Neis et al., 2020; Rubic et al., 2022). With each varying specialty and physician, was reported varying opinions and treatment plans resulting in poor communication, collaboration and ultimately fragmenting care (Khraisat et al., 2017; Neis et al., 2020).

Congruently, nurses report the effect of multiple physicians is considered as having negative effect on family members with inconsistent communication, conflicting opinions and confusion about direction of care (Khraisat et al., 2017). Subsequently, resulting in nurses feeling poorly prepared on what information to provide to families (Iranmanesh et al., 2016; Khraisat et al., 2017). Similarly, Rubic et al. (2022) reported that ICU physicians felt relief when a common stance was decided on amongst PICU physicians, however found this was less likely to occur when EOLC discussions were had involving multiple specialty teams.

Theme 4: Family Denial

A major theme that was identified amongst four studies, was the family members difficulties coming to terms with their loved ones poor trajectory (Bogetz et al., 2020; Iranmanesh et al., 2016; Khraisat et al., 2017; Lewis-Newby et al., 2020). Multiple studies report nurses in particular convey families exhibiting emotions of anger, frustration and anxiety towards healthcare professionals (HCP) when caring for a dying child (Lewis-Newby et al., 2020; Kraisat et al., 2017). Whilst death in children can be difficult to come to terms with as children are perceived as youthful, healthy and having a lifetime ahead of them (Iranmanesh et al., 2016), a familys inability to come to terms with their childs poor prognosis can be distressing for HCPs who feel they are prolonging suffering (Rubic et al., 2022).

A prominent factor acknowledged, is the effect culture and religion play in the acceptance of a childs poor prognosis (Iranmanesh et al., 2016). Three studies located in Iran and Croatia, discuss how the effect of religion and culture prevent families in accepting the inevitability of death (Iranmanesh et al., 2016; Hasanpour et al., 2021; Rubic et al., 2022). Furthermore, as identified by Neis et al. (2020) and Iranmanesh et al. (2016) research, in a death-denying society, where technology plays a large part in medical advancements enabling treatment and life prolongation of illness it is not difficult to understand why families struggle to come to terms with their childs poor prognosis.

Theme 5: Lack of Legal Supports:

A key barrier to transitioning from active treatment to EOLC identified particularly by physicians, was the limited legal and ethics support available (Carnevale et al., 2021; Iranmanesh et al., 2016; Rubic et al., 2022; Seino el al. 2019). Troubled by the lack of EOLC guidelines and legal supports in place, physicians expressed fear of criminal charges if treatment was directed towards EOLC (Carnevale et al., 2021; Iranmanesh et al., 2016; Seino et al., 2019). This was too prominent in countries where withdrawal of care is a taboo topic (Iranmanesh et al., 2016). It was reported that physicians felt they would be seen as hastening death in comparison to supporting comfort and prolonging suffering (Iranmanesh et al., 2016; Rubic et al., 2022). Carnevale et al. (2021) describes one physician reporting that they were less forthcoming with information to the family in concerns of criminal prosecution. Rubic et al. (2022) identified that legal and ethical supports would aid with shared decision making.

Theme 6: Absence of Available Education

A prominent theme identified amongst three research articles, was the limitation education plays on EOLC barriers. Experienced nurses stated that providing quality EOLC was predominately learnt through time and experience, consequently resulting in emotional distress and negative EOLC experiences for both nurses and families (Hasanpour et al., 2021). It is these experiences that are described as resulting in feelings of powerlessness, avoidance of EOLC situations and conversations (Seino et al., 2019). It was too evident, that physicians felt the lack of education resulted in them feeling unprepared and overwhelmed particularly in regards to communication to delivering bad news and discussing EOLC (Seino et al., 2019).

Thus, limitations in education programs were strongly conveyed by both nurses and physicians stating they felt unprepared when caring for families where transition from active treatment to EOLC was expected (Iranmanesh et al., 2016; Hasanpour et al., 2021).

Discussion:

Through the identification of nine qualitative research articles, this integrative review identified several barriers to the implementation of EOLC to patients within PICU. Each major identified theme was supported by multiple research articles conveying that despite variation in country locations, similar themes were identified.

Organisational barriers including the involvement of multidisciplinary teams and legal support were prevalent amongst literature as barriers to EOLC within PICU. Early involvement of multidisciplinary teams to support families through what is deemed as one of the most tragic times in life, was identified to being key to establishing sound relationships between both HCPs and improve family to child relationships (Lewis-Newby et al., 2018). Utilising expertise supports such as social workers, psychologists and spiritual leaders was noted to improve relationships and particularly support families facing difficult medical decisions or experiencing conflict or denial regarding their childs prognosis (Lewis-Newby et al., 2018).Similarly, a major theme was lack of legal support when redirecting care to EOLC. With many physicians challenged when presented with complex EOLC experiences, the lack of involvement from legal and ethical supports placed strong burden both morally and ethically, with some physicians reporting being less forthcoming of information and hesitant to redirect care (Carnevale et al., 2021). Additionally, physician related conflict was prevalent with the involvement of multiple physicians and noted to have influence on implementing EOLC (Hasanpour et al., 2021). The WHO (2020) emphasises the need for policy when questioning EOLC. It is stipulated that policy assists to overcome barriers such as physician inexperience, improves medical consensus and alleviates communication challenges (WHO, 2020). Whilst Seymour & Clark (2018) discuss the failure of the implementation of the Liverpool pathway in the adult population which aimed to create a guide to make the implementation of EOLC a more black and white decision. The pathway was scrutinised in the media, stating mortality cannot be diagnosed and thus removed (Seymour & Clark, 2018). Opposingly, WHO (2020) acknowledges policy and guidelines cannot be seen as a on-size-fits all process. Michelson (2018) concurs, further stipulating guidelines must reflect current literature findings and obtain clear and concise expectations. Furthermore, implementation of policy ensures workplace values are upheld, legal and ethical guidance and assists to remove decision ambiguity (Michelson, 2018).

Through identification of various barriers, research calls for the need of EOLC education specific to PICUs (Brooks et al., 2017; Lewis-Newby et al., 2018; Seino et al, 2019). Within Australia, tertiary education is required for all HCPs, however, this review strongly highlights the lack in available EOLC education to those within the PICU (Seino et al., 2019). Research stipulates that EOLC skills are currently acquired through on the job experience, highlighting the negative emotional effects experienced by both HCPs and family members when suitable training is not instilled (Hasanpour et al., 2021). The WHO (2020) too, noteworthily, discuss the lack of education resources in fields concerning to EOLC. Furthermore, the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health care (2016), highlights the complexities associated with EOLC situations, stipulating that an educated and skilled workforce is key to ensuring enhanced QOL and form sound relationships. Where EOLC education lacks, HCPs report feelings of powerlessness, feeling unprepared and avoiding EOLC situations, education and training has been described as being paramount to overcoming these challenges (Brooks et al., 2017; Iranmanesh et al., 2016; Hasanpour et al., 2021).

Limitations:

This integrative review acquires multiple limitations. Key limitations illustrated during critical appraisal identified weaknesses amongst rigor and validity of chosen studies through small sample groups in each study preventing generalisability of research findings. Firstly, six out of the nine studies utilised questionnaires as their predominate method. Although some incorporated open-ended questions, potential quality data may have been missed and potential barriers not identified. Additionally, whilst Australia is noted to comprise of numerous cultures and religions, as discussed by the ANZICS (2014), EOLC encompasses quality of life and reducing pain and suffering to the individuals. However, as discussed by Iranmanesh et al. (2016) and Rubic et al. (2020), cultural variances between countries on death and dying may vary. Thus, making EOLC barriers identified within this review difficult to generalise. Finally, this review highlights the limited amount of research into EOLC in PICU, identifying only nine relatable articles. Correspondingly, three articles were not set solely within PICU environment. Therefore, preventing total generalisability of EOLC barriers to the PICU environment. Specifically, given the variation of patient presentation and acuity in comparison to other paediatric hospital areas (Lewis-Newby et al., 2018).

Implications for Healthcare Practice:

This integrative review highlights a noteworthy gap in both literature and practice, in regards to overcoming barriers associated with EOLC within the PICU. The limited number of articles retrieved from the review, identifies the lack of current available research performed within the PICU on identifiable barriers to EOLC. Specifically, given the PICUs highly stressful and emotional environment and unique and complex nature of children presenting to the PICU, more research is required to identify barriers specific to the PICU environment. Correspondingly, nil Australian articles were acquired. This, therefore calls for research to be performed specifically within Australian PICUs to identify the prevalent barriers. This limits cultural variation that has been identified within this review.

Review into educational resources in implementing education on EOLC, specific to PICUs where EOLC is a prominent cause of emotional distress experienced by HCPs and families (Brooks et al., 2017; Carnevale et al., 2021). Literature conveys that EOLC education should be multidisciplinary and focus on the complexities, ethical challenges and communication to ensure all those HCPs involved in EOLC within PICU are equipped with the appropriate skills and knowledge (Iranmanesh et al., 2019; Seino et al., 2019)

In March 2021, the Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety (2021) released its Aged Care Quality and Safety report. The report comprised of key recommendations for palliative care and EOLC improvements, one in which was mandatory EOLC training for aged care workers (Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety (2021). End-of-life care plays a vital role within PICUs, to providing a high level of care and ensuring best QOL is provided (Butler et al., 2019). It gives question as to why EOLC education is not mandatory for HCPs working within the acute care setting, or more importantly PICU. Conversely, this reaffirms the limited research undertaken in Australia regarding EOLC within PICU (Michelson, 2019).

Conclusion:

When examining the barriers related to implementing EOLC within PICUs, an integrative literature review was undertaken and identified six key barriers. These barriers were identified through nine qualitative studies that examined the perspectives of HCPs and families through questionnaires and interviews. The identified barriers included; challenges with communication, limitations in multidisciplinary team involvement, involvement of multiple physicians, family denial, lack of legal supports and absence of available education. Whilst limitations to research articles were identified, such as unable to generalise results due to variation in culture and small sample sizes, the review too highlighted the limited amount of available research based on EOLC in PICU, but too highlighted the need for further research within the Australian PICU environment. Finally, the integrative review strongly conveyed the need for enhanced education programs to empower HCPs and ensure good EOLC practices, but additionally, provide guidelines and policies to support physicians in their EOLC decisions.

Are you struggling to keep up with the demands of your academic journey? Don't worry, we've got your back!

Exam Question Bank is your trusted partner in achieving academic excellence for all kind of technical and non-technical subjects. Our comprehensive range of academic services is designed to cater to students at every level. Whether you're a high school student, a college undergraduate, or pursuing advanced studies, we have the expertise and resources to support you.